John Plamenatz on ‘Historical Inevitability’

Item No. 24.

John Plamenatz

A letter to Isaiah Berlin from 1955

By Zachary Larsen

John Plamenatz (1912–1975) and Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997) led something like parallel lives. They were born three years apart, both in Eastern Europe (in its broadest sense). Berlin was born into the Jewish merchant class of Russian Latvia – a minority within a minority. Plamenatz, a Montenegrin, was born while his country was still an independent kingdom. By the age of six he too belonged to a minority, as Montenegro was absorbed first by Serbia and then into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later renamed Yugoslavia). Forced to emigrate by turmoil on the continent – Plamenatz by the First World War, Berlin by its by-product, the October Revolution – both found their way to England, where they attended public school and Oxford, were naturalized as British subjects, and spent the rest of their lives. Both saw their home countries succumb to communism, to which they were similarly hostile, and to which both counterposed a kind of liberalism. Each was elected a fellow of All Souls College, where Berlin was later appointed Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory. His successor in that chair was Plamenatz. By then both were among the most distinguished writers on political ideas in the English-speaking world. The present item records one of their intellectual encounters, revealing their sympathies and differences as well as a shared interest in historiography.

Read more below….

Source: John Plamenatz to Isaiah Berlin, 2 April 1955,

Papers of John Plamenatz, Archive of European Intellectual Life, St Andrews ms39129/12/4

The Institute thanks Henry Hardy and Anne Wochiler for their help with this item.

We hope to publish more items from the Plamenatz and Berlin papers at St Andrews in future posts.

Isaiah Berlin

Continued…

Berlin was earlier in arriving at All Souls, becoming its first Jewish fellow in 1932. Principally a philosopher in these years, he formed a circle of friends and intellectual sparring partners including J. L. Austin, Stuart Hampshire, and A. J. Ayer, at the same time publishing important essays on logical positivism and the linguistic turn.

A year into his fellowship he was invited to write an intellectual biography of Marx, which he published (after lengthy gestation) in 1939. It was the only monograph he ever wrote. In another sense, however, it set the tone for the rest of his career, for he soon made a conscious conversion from analytical philosophy to the history of ideas. From the end of the Second World War to his death in 1997 his intellectual energy was spent chiefly on essays and lectures in this genre, spanning subjects as various as Machiavelli, Vico, the Romantics, Tolstoy, and Tagore.

In March 1936 Berlin reported, in a letter to his friend, the poet Stephen Spender, that All Souls had elected ‘someone even more terrifyingly un-English than I am, namely a Montenegrin called J. Petroff Plamenatz’. Alluding to the reputation of the Balkans, he added: ‘I expect he will do a lot of terrorism at college meetings. Comes of an old Cetinje [the old Montenegrin capital] family & looks a brigand’.

Berlin was even less charitable in another letter, written later that month. One fellow ‘almost swooned’ on hearing of Plamenatz’s nationality, Berlin recounted. Another said ‘he sh[oul]d be searched for bombs before entering college meetings’. Berlin himself added that his new colleague was ‘repulsively ugly & looks like a currant & dates merchant. And is a philosopher’.

As Berlin hinted, Plamenatz was descended from a long line of Montenegrin peasant warriors. His father, who came to be foreign minister of the independent kingdom, was said to be the first man in the family to die elsewhere than on the battlefield. With him the young Plamenatz went into exile in 1917, first to France, then to England, where he was sent at the age of seven to Clayesmore School (at the time in London). From there he proceeded to Oriel College, Oxford to read philosophy, politics, and economics. He stayed for a DPhil, but his thesis was failed by his examiners, a decision later condemned by Berlin as ‘perhaps the greatest miscarriage of academic justice known to my generation’.

It was Berlin too who noted the ‘singular irony’ that this very thesis was the grounds on which Plamenatz was elected shortly thereafter to All Souls. Published in 1938 as Consent, Freedom and Political Obligation, it was in Berlin’s view ‘probably the best work on political theory produced by anyone in Oxford since the First World War’. In contrast to Berlin, this was to be the first of many books Plamenatz wrote, including his most famous work, the two-volume Man and Society (1963).

Notwithstanding his initial jibes – perhaps in part an affectation – Berlin seems to have got on well with Plamenatz. Their correspondence – part of which is in the Archive of European Intellectual Life at St Andrews – was friendly. And though in Berlin’s view they were rivals for the Chichele chair in 1957, he spoke (in a letter to another friend) of Plamenatz’s ‘very worthy and decent candidature’. Berlin would read a fond tribute at Plamenatz’s memorial service in 1975 (republished in Personal Impressions) and wrote the latter’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. (His correspondence with Plamenatz’s widow about the details of her husband’s life is also held at St Andrews.)

A further proof of amity and intellectual engagement is the document presented above: Plamenatz’s comments on Berlin’s long essay ‘Historical Inevitability’, sent to the latter in 1955.

Berlin’s essay began as the Auguste Comte Memorial Lecture, delivered at the LSE in May 1953. The lecture’s namesake, and its endowment by the (Comtian) English Positivist Committee, did not discourage Berlin from opening with an attack on Comte’s

grotesque pedantry, the unreadable dullness of his writing, his vanity, his eccentricity, his solemnity, the pathos of his private life, his insane dogmatism, his authoritarianism, his philosophical fallacies, all that is bizarre and utopian in his character and writings …

Likewise undeterred was the occasion’s chair, the conservative Michael Oakeshott, whose introduction was marked by ironic barbs directed first at Comte and then at Berlin himself. ‘Listening to him’, said Oakeshott of his guest, ‘you may be tempted to think that you are in the presence of one of the great intellectual virtuosos of our time, a Paganini of ideas.’ In other words, Berlin – who had lately gained fame through a series of hugely popular radio lectures – was a showman with little substance.

‘A very bitchy introduction’, Berlin later recalled. Unnerved, he fumbled his way through the lecture, as Michael Ignatieff describes in his life of Berlin:

The text was much too long for delivery and he began abridging it as he went, wildly putting pages aside, struggling to keep the argumentative thread together, talking in an ever faster, high-pitched gabble. When he staggered to a conclusion, the reactions were perfunctory and polite and he came away, not for the last time, with the uneasy feeling that his peers were asking themselves whether his reputation was deserved.

He never forgave Oakeshott the humiliation, stating that they could not be ‘friends, or even opponents bound by a mutual feeling of respect’. (His own assessment of Oakeshott was ‘a feeble heir of Montaigne & Burke, with not one idea, or even formulation, to call his own’.)

Nevertheless ‘Historical Inevitability’ was revised and published in 1954. It was a long, somewhat rambling, and provocative essay on the philosophy of history – specifically the question of determinism. Is history made by individuals, or is it governed by vast, impersonal forces? To Berlin, it seemed, a growing number of historians and other thinkers were leaning towards the latter. This tendency led in turn to the view that the people of the past must be exempt from moral accountability for their actions. This for Berlin was an alarming trend, and he set out over some eighty pages to refute it.

Anti-determinism was not a new subject for him. He had discussed it as early as ‘Freedom’, a prize essay he wrote at St Paul’s School at the age of eighteen (reprinted in Flourishing: Letters 1928–1946). There he condemned ‘the materialistic philosopher of our days’, whose picture of the universe as ‘a piece of machinery’ was ‘the boldest and the most merciless self-depreciation which man ever enunciated’. Among the perpetrators of this degradation, he thought, were Freud, Bergson, Mendelian biologists, ‘American industrialists’, and Italian fascists. Perhaps above all there were the communists, with their stress on ‘the overwhelming, and indeed, exclusive importance of the physical or economic life’ and their hope that ‘individualism might be utterly eradicated’.

Berlin was able to expand on this last point in his biography of Marx, of which a whole chapter was devoted to historical materialism. Here Berlin was more balanced. His aim was to give a fair-minded account of Marx’s theory, and he succeeded. To be sure, he made judgements, some of them critical. Marx’s utterances on determinism could be contradictory, and his practice as an historian did not always live up to his scientific ideal. Historical materialism was ‘by no means a wholly empirical theory’. Its hypothesis was not made ‘less or more probable by the evidence of facts’. Rather this probability was determined by ‘a pattern, uncovered by a non-empirical, historical method, the validity of which is not questioned’.

But insofar as Berlin took a stance in this chapter he was largely positive. Regardless of its validity, historical materialism was ‘without parallel’ in the clarity of its questions, its methodological rigour, and its ‘combination of attention to detail and power of wide comprehensive generalisation’. Its intellectual impact had been huge. Marx had a genius for turning ‘into truisms what had previously been paradoxes’, and these achievements had been ‘necessarily ignored in proportion as their effects [had] become part of the permanent background of civilised thought’. (Berlin would later apply similar praise to Comte, writing that if the positivist’s works were ‘today seldom mentioned … that is partly due to the fact that he had done his work too well’.)

By contrast ‘Historical Inevitability’ – where Berlin’s goal was not exposition but polemic – gave full vent to his feelings on the subject. He revived his attack on Freud, Marx, and their respective followers. Bergson and Mendel were spared, at least by name, but the range of targets was greatly widened, in both ideology and time. D’Alembert, Carlyle, Condorcet, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Fichte, Gobineau, Hegel, Herder, Hitler, d’Holbach, Jung, Spengler, Tolstoy, Toynbee – and all the theorists of custom, race, nation, class, religion, technology, and climate as determinants of history – each came under Berlin’s fire.

All these theories, he wrote, were ‘profoundly anti-empirical’. Echoing his earlier criticism of historical materialism, Berlin asserted that these were not theories subject to evidential proof or disproof but were ‘a metaphysical attitude’, a kind of teleology by which ‘to explain a thing … is to discover its purpose’. Moreover the corollary of determinism in history was ‘the elimination of the notion of individual responsibility’ and the adoption of moral relativism. And so it became futile to assign responsibility for events to individuals, to use them as ‘examples or deterrents’ or ‘derive lessons from their lives’.

For Berlin all this was wrong. He sought to show it was so through sometimes lengthy discussions of ordinary language, the possibility of total objectivity in history, the differences between science and historical method, and the failings of sociology. To accept these determinist doctrines, he wrote, would be ‘to do violence to the basic notions of our morality, to misrepresent our sense of our past, and to ignore the most general concepts and categories of normal thought’.

He ended by asking why the determinist view had proved so seductive. The reason, he proposed, was ‘a desire to resign our responsibility’. Determinism removed all sense of guilt and sin. ‘It is one of the great alibis, pleaded by those who cannot and do not wish to face the facts of human responsibility … .’ How much better to transfer our sin to ‘an impersonal plane’. ‘We are soldiers in an army, and we no longer suffer the pains and penalties of solitude; the army is on the march, our goals are set for us, not chosen by us … .’

The essay was widely reviewed. The bylines included some then and later well-known names: H. B. Acton, E. H. Carr, Isaac Deutscher, Henry Fairlie, Ernest Gellner, Irving Kristol, Reinhold Niebuhr. Almost all spoke of Berlin’s eloquence, and most praised his arguments as well, though there were interesting dissenters (Fairlie, Gellner). Deutscher, whom Berlin would later blackball from a chair at Sussex on account of his communism, wrote a particularly fair and perceptive review. Berlin’s essay was a ‘brilliant, irresistibly eloquent tirade’, and was strong on the unscientific nature of history and the cowardice that underlay much determinism, but ‘it attempts too much and achieves too little’:

Mr Berlin protests on almost every page against the generalisations and abstractions of others, but he himself sins in this respect to quite an extraordinary extent. He lumps together scores of philosophical ideas and systems, determines in a few sentences of sweeping generalisation what is their ‘common denominator’, and then roundly condemns them all. He throws the heads of nearly all the great philosophers and historians of antiquity and modern times into one vast bag, heaping the same accusation on all of them, and then he hurls them down with one magnificent gesture from the Tarpeian rock. Only two philosophers, I fear, survive the great execution: Mr Karl Popper [whose Poverty of Historicism, also an attack on determinism, had been published in 1944–5] and Mr Isaiah Berlin.

(David Caute speculates in his book Isaac and Isaiah that this review was ‘the killer event in Berlin’s attitude to Deutscher’.)

In the years since his first acquaintance with Berlin, Plamenatz had written much on Marx and his ideological heirs: a monograph – German Marxism and Russian Communism (1954), which Berlin read in manuscript – as well as two long pamphlets for the lay reader and several articles and reviews. In these works Plamenatz placed historical materialism at the centre of Marxist thought. He treated the materialist conception at some length, focusing on its vagueness and other inadequacies. One of his more memorable criticisms was of the inaptness of the base–superstructure metaphor: ‘If a building has a foundation of brick it does not follow that the upper part must be built of stone and not of wood.’ Also significant, in light of the comments presented above, is his point about determinism and its effect on the mind. Far from driving its believers to resignation, it was a source of strength and inspiration.

From 1955, the year after ‘Historical Inevitability’ was published, we find the following letter from Plamenatz to Berlin:

Dear Isaiah,

You may remember that I threatened to write to you about your lecture on Historical Inevitability.

Please forgive me the length of my comments, or rather take it as the measure of my interest in your lecture. I enjoyed it immensely. It is about a subject that very greatly interests me, and that is why my comments, which my wife has typed so that they may be legible, are so long.

I have not bothered to tell you where I agree with you, as I do to a very considerable extent. I have tried to explain as clearly as I could where I differ from you. I feel, however, that I may on some occasions have misunderstood you. I hope I have not done so, but if I have, it may still interest you to see in some detail how you have been misunderstood. I often find even that instructive and helpful, when I read other people’s comments on what I have written.

Your lecture is wonderfully well written; it is a real pleasure to see arguments put with so much vigour and persuasiveness. You make an important subject seem important.

Last term I saw almost nothing of you; I hope to be luckier next term.

Yours

John

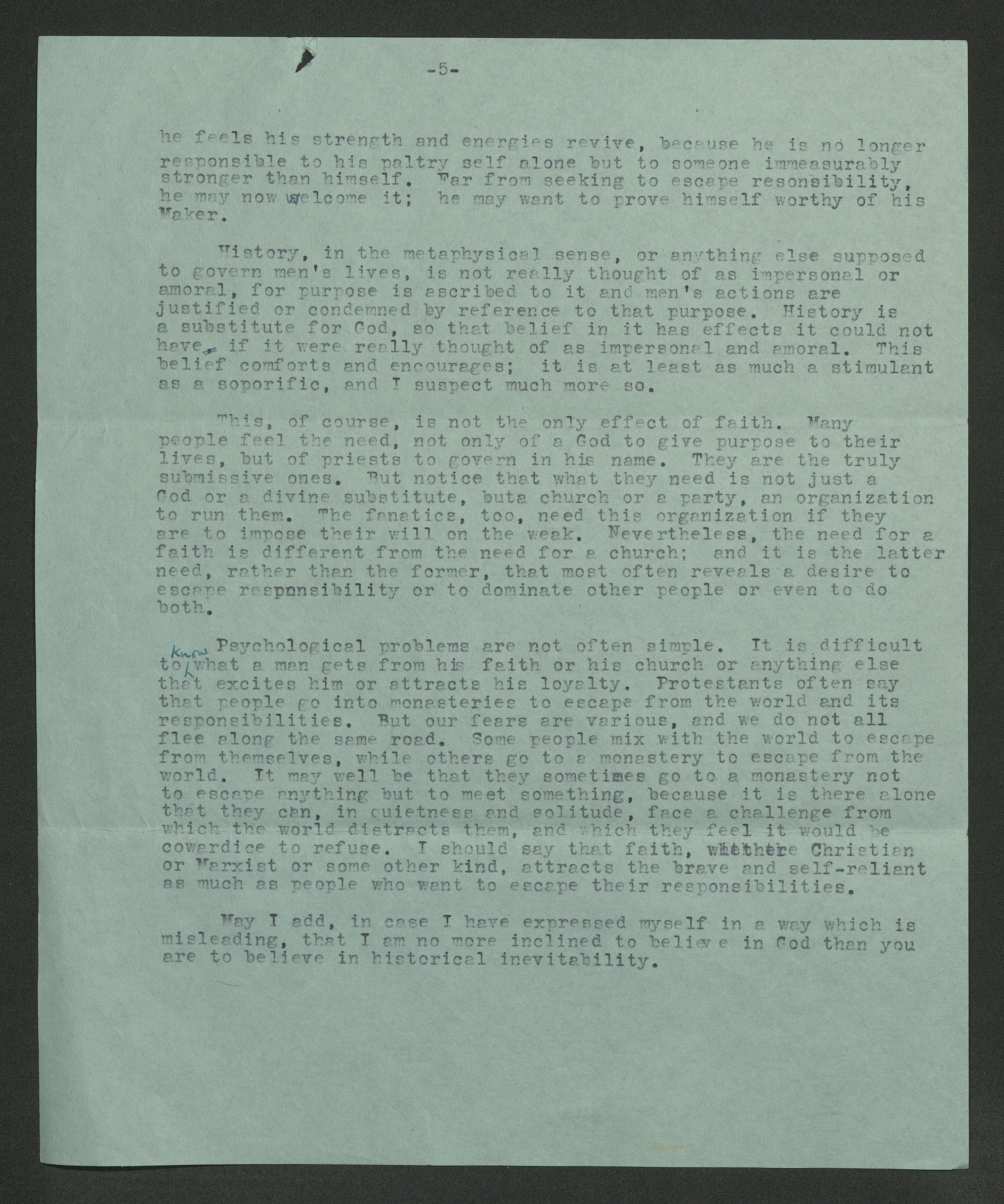

Attached was a five-page commentary, typewritten with corrections in Plamenatz’s hand. His criticisms of Berlin’s essay fall under four heads: (1) Berlin’s argument that ordinary language is incompatible with determinism; (2) the implications of moral responsibility for freedom of choice; (3) Berlin’s assertion that moral objectivity is impossible for the historian; and (4) the reasons for which people subscribe to the determinist position.

The last section is the longest and of greatest interest. Plamenatz found Berlin’s aetiology – that people believe in historical inevitability to shirk responsibility – simplistic. Wrong though it is, determinism attracts ‘the brave and self-reliant’ as much as it does the craven. Parallels are drawn with the psychology of religion, and Plamenatz remarks on a paradox in Christianity: Calvinism, with its doctrine of predestination, has been a better friend to freedom than has the Catholic Church. (Some may find this redolent of Hume’s essay ‘Of Superstition and Enthusiasm’.) He ends by clarifying that ‘I am no more inclined to believe in God than you are to believe in historical inevitability’.

This letter also serves to remind us that Berlin and Plamenatz, though not as concerned with context as the Cambridge School, were far from unhistorical. In fact Plamenatz’s student papers (St Andrews ms39129/1/2) are full of notes from his extensive reading in history: Huizinga’s Waning of the Middle Ages, ‘Russian Rulers from Ivan the Terrible’, and much on modern France. Berlin’s early reading likewise consisted of Macaulay, Spengler, and other historians. At Oxford Berlin attended R. G. Collingwood’s lectures on the philosophy of history, which probably formed part of the foundations of his posthumous classic The Idea of History (1945), while Plamenatz progressed from PPE to History, in which he took a first. And not long before the letter above, Plamenatz had written a whole book of political history: The Revolutionary Movement in France, 1815–71 (1952). Their exchange on historical inevitability was only an episode in a lifelong concern for both men.